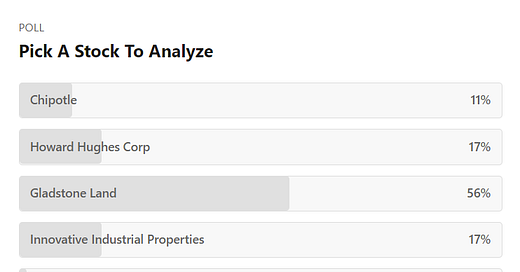

We Have a Winner

It looks like Gladstone Land won the original competition. I’m planning on taking the next week off (and trying not to melt into a puddle as it is WAY too hot in Carl Junction at the moment). Combination of chemo week and reading the Gladstone 10K (recommended homework for those following along at home). The 10K is around 160 pages, so we might need to break it into parts.

That said, here are the results

If this is a success, we’ll hit up Howard Hughes next as it is one that I’d like to look at in more detail as well.

Peloton And Stock Compensation

One of the danger points of stock compensation is that stock prices can run quite a bit higher than one would expect…followed by a large fall from grace. A great example of this is one of our previous highlighted companies — Peloton. You can find the story of what happened on CNBC.

In one of the internal memos, Peloton told employees that eligible team members will have their post-IPO options repriced to Peloton’s closing price on July 1 of $9.13.

As an example, Peloton said options granted granted on March 1 had an exercise price of $27.62, meaning they were “underwater,” and employees were not benefitting financially until the stock passed that threshold. After the repricing, Peloton employees will be able to exercise their options after the price passes $9.13.

I guess they really wanted to drive home that the options were granted since they said it twice. 🤣 Okay, seriously though, this illustrates one of the problems with stock compensation that a lot of companies are dealing with. When the stock price drops by enough that the option is unlikely to be beneficial, what does the company do?

If Peloton were to say “Sorry, but the deal was made at $27.62 and you accepted the incentive compensation”1 then the incentive is probably a lot less relevant. You had thought that if the stock price went up you were going to benefit. However, now the stock price has fallen down to $8.48 and employees are thinking “even if the stock price triples, it is only going to be worth $25.44…I’m not seeing that bonus.” So, the incentive benefit is gone. If the purpose of incentives is to drive employees to work harder to add value, your incentive no longer is effective. This is a problem for Peloton and their ability to retain key employees. Remember that the people who leave are likely going to be the ones who are most employable elsewhere…not exactly a great business strategy.

On the other hand, let’s say that employees screw up (and this is not a knock on any Peloton employee) and destroy value, but their options are repriced, where was the incentive in the first place? Now, the stock has fallen by more than 67% and you are resetting their strike price quite a bit lower. This seems to make the incentive one where the company is in a damned if they do and damned if they don’t situation.

What is the right decision? I honestly don’t know. Stock options like this reward volatility (one of the key inputs into option pricing models is how volatile the stock is…the higher the better). They also reward value creation (increasing the value of the stock is also directly going to move the value of the option higher). If you are going to use stock options to create an incentive system for employees, how do you balance the risk of rewarding employees for creating value with the lack of incentive for stock prices getting demolished? This is going to be an issue for quite a few firms in the current marketplace and I’m glad that I’m not making the decision. My solution might be to allow them to keep the original options and grant them a lot fewer repriced options, but I haven’t really thought through the implications of that startegy.

Tweet of the Week

This was a Twitter Poll question and the options included 2 times, 4 times, or 10 times. I got the right answer (🎉🎉) without looking, but my question was how do they control for quality of house? Consider this story from the Chicago Tribune

In 1900, for instance, a typical American new home contained 700 to 1,200 square feet of living space, including two or three bedrooms and one or (just about as likely) no bathrooms. It was probably a two-story floor plan.

At the turn of the 20th Century, more than 20 percent of the U.S. population lived in crowded units, with entire families often sharing one or two rooms. Most homes were small, rural farmhouses and lacked many basic amenities, complete plumbing and central heating chief among them.

Then, follow that up with the update from more modern times

The average single family house in the United States has overall increased in size since 2000. It reached its peak of 2,467 square feet in 2015 before falling to 2,261 square feet by 2020.

I’m guessing that the wifi routers used in 1900 might (just maybe) be a little less powerful than the ones in 2020 (narrator — there were no wifi routers in 1900). Heck, the houses in 1900 lacked “many basic amenities” such as “plumbing” and “central heating” to name a few.

In 1900, there were only 45 states in the US (Oklahoma entered in 1907, New Mexico in 1912, Arizona in 1912, Alaska in 1959 and Hawaii in 1959). For the record, in 1888, the US had only 38 states. Black American home ownership has it’s own set of problem as this CNBC article illustrates. Then location changes, both across the country and within cities also played a big part.

What this means is comparing home prices from 1900 to 2020 is probably a pretty big stretch even for those that specialize in trying to hold the data constant. This data was based on the Case-Shiller Home Price Indices and you can see the methodology paper here that explains the process. One interesting note is that the index was formed in 1987 and uses a “repeat sales method” of including houses. Unfortunately, this is going to create a bit of a bias as it is not including every house. Consider this comment from “Repeat Sales House Price Index Methodology”

A third measure is how well the index represents trends in the overall market. Previous research has shown that repeat sales homes are fundamentally different from single sales; in light of this work, it is difficult to argue that traditional repeat sales indices can truly represent the housing market. While all of the indices (including the median index) exclude houses that do not sell, the median and autoregressive index do include single sales which can make up a large proportion of total sales. Therefore, in this regard, these two indices are more representative of the housing market.

Separating Quality Improvements from Quantity is Not Easy

The main point of this ties back into my belief that the world is getting better at a very fast rate, but we as a species tend to focus on the “what could/is going wrong” rather than the “what could/is going right” side of the equation. This makes perfect sense as our day-to-day existence is based on preventing bad things from happening and keeping up with the 1001 different tasks at hand. We rarely have time to stop and appreciate all the huge positives that have impacted our lives over the last 10-150 years. Things like (and this is just a VERY small random sample)

Apple releasing the iPhone in 2007

Traveling to space in 1969 to land on the moon (I was just about to turn 1)

Bloodletting was finally stopped in the early 20th century (apparently still included in the text in the 1923 edition of The Principles and Practice of Medicine)

Life expectancy increased from from 32.5 years for Black men in 1900 to 68.7 years in 2000. White men were expected to live for 46.6 years in 1900 and 74.7 in 2000. Those numbers are currently up to 76.61 for men and 81.65 for women in the US.

Flat screen TVs, internet access, medical advances, technological advances, etc.

All of these things have made the world a much better place. It’s just that we don’t spend much time thinking about them. Instead, we fret about things that are both significant and insignificant in our lives. Things like how are we going to afford the latest medication, how expensive gasoline is, etc. These things matter far more to our day-to-day lives and seem more important. I’ve done the same thing myself many times. I get it. Just remember to take a moment to look at the big picture because we are doing quite well when you look at decades instead of just the current week.

Think of housing and look at the numbers from 1910 to 2015

US-wide, homes built in the last 6 years are 74% larger than those built in the 1910s, an increase of a little over 1,000 square feet. The average new home in America, be it condo or house, now spreads over 2,430 square feet. It is also important to note that, parallel to the rise in living space, households have been getting smaller over the same period. In 2015, the average number of people in a household is 2.58, compared to 4.54 in 1910.

Then, think about plumbing, air conditioning, and all the other modern amenities available now vs. in 1910. Housing costs have gone up not just because housing is more expensive, but it is also a LOT, LOT nicer now.

If we think about economic numbers (the macro story), you quickly realize that just like in finance, no one number is magic. Inflation came in this month at a 9.1% increase. However, that tells us what happened in the past. We want to know what is going to happen going forward. Granted, inflation doesn’t just jump up to 9.1% this month and fall to -1.5% next month…there is definitely a high correlation between one month and the next. It IS information, but it is a very small piece of a very large puzzle.

It was higher than expected (it came in up 1.3% vs. the 1.1% that was expected). Notice that the difference there is incredibly small, 0.2%. Assuming you spend $5000 a month, your budget went up by $65 instead of by $50. Granted, $15 isn’t nothing and not everyone is spending $5000 a month, however that is for the person that buys the products in the CPI basket in the same proportion as the basket (which is essentially no one).

This is not to say inflation is not a problem as it clearly is. Instead it is saying that a big part of the problem is not just what is happening but how we feel about what is happening. Is inflation making me rethink a purchase that I was planning to make? How are we (as a society) responding to the increase in prices? How long is inflation going to be higher than normal? Another month or two or another year or two? These will play a part as well. As I said…economics is not easy!

Taking the time and effort to focus on how life has improved is not easy. It’s much simpler to think of day-to-day changes. That said, it is something we all need to take some time to do. The question of whether or not you’d rather be alive in 1922 or 2022 should be one of the easiest questions to answer for the majority of people.2 100 years is a relatively short time period, but the difference is incredible in quality of life.

The stock price closed that date at $27.62

Granted, there are a few people that would answer 1922, but I’m guessing most of them (not all) would change their minds in a few days. A few would actually be happier then, but probably a very small percent.