Luck vs. Skill

Check the Bottom of The Page

Even if you are not in the mood for this week’s substack, be sure to check the last item which is going to lead to the next several weeks’ activity. No promises for an updated publication each week as we’ll see how the experiment progresses.

Luck vs. Skill

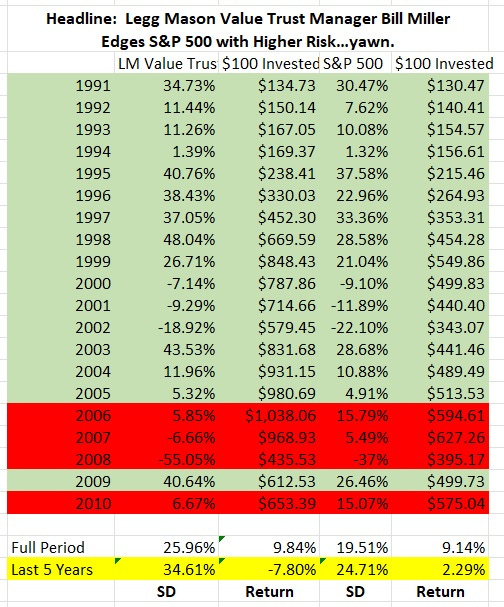

Let’s start with a slide show that I used when teaching Investments class. One of the investment gurus from our recent past is Bill Miller. He crushed the S&P 500 for fifteen straight years. Not five years. Not 10 years. Fifteen straight years after fees (so net investor returns) he beat the S&P 500. That seems pretty damn impressive!

Some years were really close (such as his 7 basis point beat in 1994) while others were runaways (like his 1946 basis point crushing in 1998). However, if someone outperforms the S&P 500 for 15 years in a row, it has to be more than luck.

Or does it?

Here are the next 5 years of Legg Mason’s Value Trust Fund.

So, he crushes the S&P 500 for 15 years in a row…then gets crushed for four of the next five years. So, for the full period he slightly outperformed the market. Although, if you jump back to our column on returns and did a dollar-weighted return, you’d probably find out that he underperformed the market because his worst years were at the end when you’ve accumulated most of your income.

However, one of the key aspects of finance is that expected return is related to risk. All else equal, the greater the riskiness, the greater the expected return.1 This leads us to ask about how risky the returns were for LMVT. Again, the story becomes a little less impressive.

If we look, not only did LMVT earn a slightly higher geometric return, but it accomplished it by taking on quite a bit more risk. Overall, there is a significant chance that this is far more of a luck aspect than it is a result of skill. Granted, Bill Miller recognizes this.

As for the so-called streak, that's an accident of the calendar. If the year ended on different months it wouldn't be there and at some point the mathematics will hit us. We've been lucky. Well, maybe it's not 100% luck—maybe 95% luck.

Differentiating Between Luck and Skill

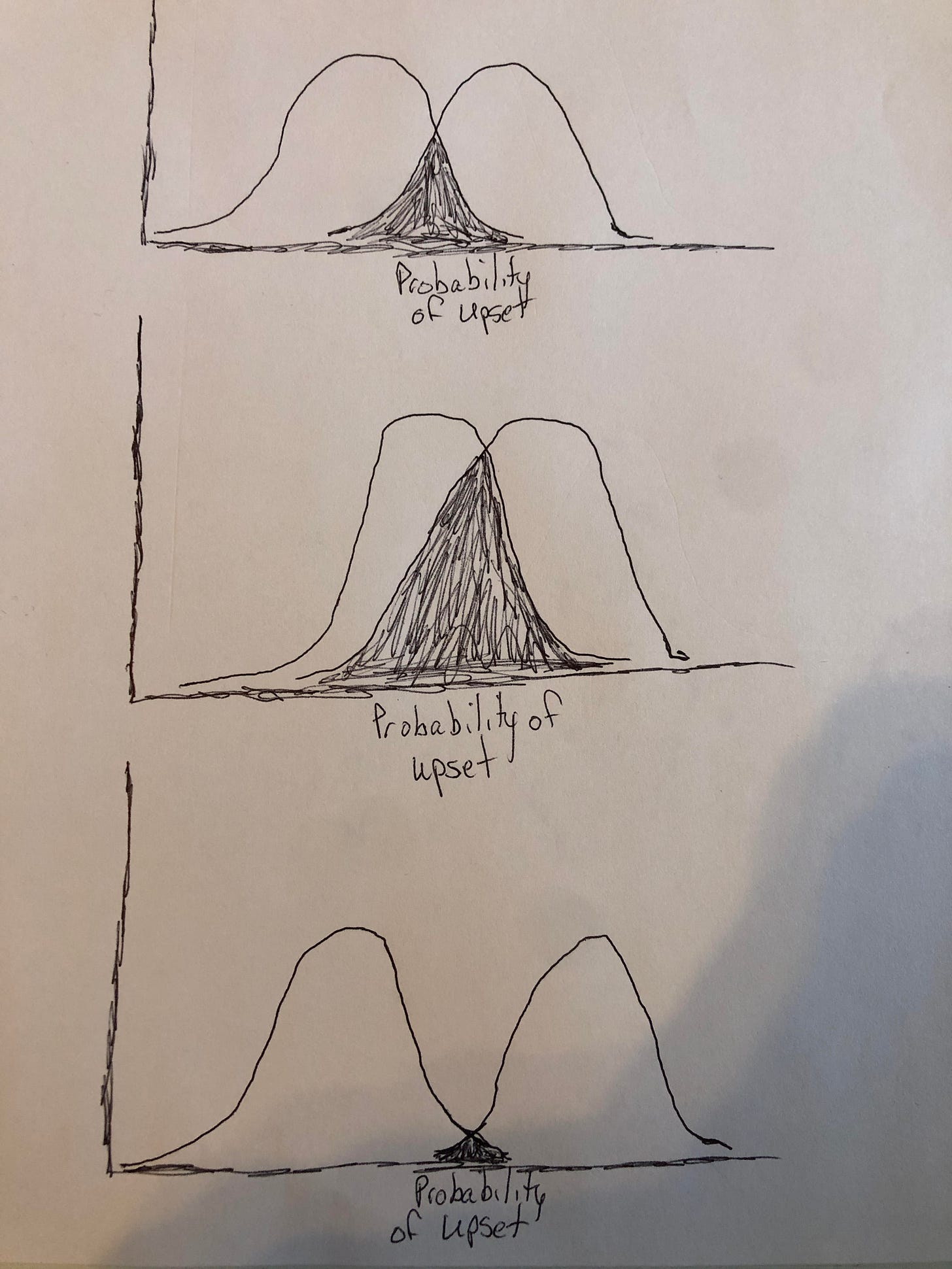

How do we separate luck vs. skill? Probably the easiest way to think about this is with standard deviation. If you think of two distributions you can see how much is luck vs. skill. Here are three possible scenarios2

The first example would be a two-player contest with the first team being a little less talented than the second team. Let’s say it is New Orleans Pelicans vs. Golden State Warriors. Golden State is going to win most of these games, but the Pelicans are going to occasionally win a few. It could be injury issues, one player shoots better than normal, lackadaisical play, or any of a number of issues. The second example would be a two-player contest with the first team being Boston Celtics and the second team being Golden State Warriors. These two teams are more evenly matched, but Golden State was better (assuming this year’s victory was not purely luck) and won the NBA Championship in 2022. There were some injury issues, Boston had far more turnovers, etc. The last scenario would be the Houston Rockets vs. Golden State Warriors. Golden State is a superior team, but there is still a chance for an upset…just a much smaller chance.

Michael Mauboussin looked at some types of competition and came up with the following diagram

If you think about this, it makes a lot of sense (although Ed Thorp may have a little different take on roulette thanks to his wearable computer…if you’re not familiar with the story, it’s worth a read). Slot machines and roulette should have a negative sum experience. In roulette, the “house” has two numbers (0 and 00) along with 36 other numbers. The house edge comes from the fact that you have a 1:38 chance of getting the number right (because of the two house numbers), but the you get paid as if there are 36 numbers. This gives the house a small edge (2 of 38 or 5.26%). Slot machines also typically pay out about 85-95% of their take.

We know that markets are pretty efficient and it is VERY, VERY hard to outperform on a risk-adjusted basis. Consider that over a 10-15 year time frame, mutual fund performance is not very encouraging. Keep in mind that these are professional investors who have the time to keep up with everything going on in markets. In other words, they are working 40+ (and keep an eye on the plus sign) hours a week to make sure that they have the edge.

Notice that the performance numbers all drop as the years go up until they are between 12.8% - 18.6% once we hit 15 years. This makes sense as funds have expenses, trading costs, etc. Indices do not. Even if you invest in index funds, you are likely to underperform the index by a small amount (although if a fund underperforms by 0.75% vs. 0.10%, you’ll feel a lot happier in the 0.10% underperformance version).

That said, there are two arguments for why individual investors may outperform. One, they are reducing costs (well, assuming they enjoy the challenge of trying to outperform which may make their time cost negative). Two, they have a broader pool of potential investments (note that small and mid-cap did better than large-cap and all US equity). By choosing to focus on small-cap and mid-cap stocks, where they can focus on firms with little analyst coverage (especially in the arena of under $2B dollars of market capitalization), there is more potential to find success (maybe). The flip side is that overtrading, poor tax planning, ignoring trading costs, unrealistic recognition of expected returns, etc. far exceed the potential benefits for the vast majority of investors.

When you get out to chess, there are chess ratings which range from 100 - 3000. If someone with a score of 2200 played someone with a score of 1000, the 2200 player would win every time (barring having a heart attack in the middle of a game, an internet disconnect, or divine intervention). There is little luck in chess.

Skill in Investing

So, how much “skill” do you bring to your investing game? Do you spend time reading and understanding the advantages/disadvantages of your investments? Can you explain why a firm has a higher expected return or a higher standard deviation? Can you explain why two investments are higher or lower correlated to each other? Do you spend time thinking about “what can go wrong?” Do you understand what moats are and how well they can be defended? Do you think about technology and how it is going to change (and how that change will alter the competitive dynamics of your companies)? Do you have a model for FCF forecasts out five years that is not based on a random number generator like ARKK funds? Research (developing the necessary skill) takes a LOT of time and effort.

Unfortunately, it is not something where the effort is merely starting up. You have to kick a lot of rocks (which often results in stubbed toes) in order to uncover potential opportunities. Then you have to continually monitor those opportunities. Once you get a portfolio that is reasonably well diversified (say 15-20 carefully selected stocks), it is going to take a lot of time to keep up with them. It is a hard game to play and the results are that you are most likely going to slightly underperform the markets.

Going Forward

One of the things we are going to do going forward is a valuation exercise. If you are reading, let me give you a few names to choose from.

Note that Chipotle has been done (but this was about 2 years ag right as COVID was hitting). You can see the YouTube videos here. Howard Hughes Corporation is a land ownership company (develops Master Planned Communities including residential and commercial properties). Gladstone Land is a farming REIT that focuses less on row farms and more on fruits (strawberries, apples, blueberries, etc.), almonds, and pistachios. Innovative Industrial Properties is primarily a cannabis REIT where the focus is on ownership of acquisition, ownership and management of specialized properties. Finally, McDonalds operates and franchises McDonald's restaurants in the United States and internationally.

The key is that these are relatively small companies (Chipotle and McDonald’s are bigger at $37 billion and $187 billion, but are still narrowly focused firms). The others are much smaller between $350 million and $3.5 billion and again have narrow focuses. The best place to start is from a small base. Also, I do reserve the right to go to the second (or third) choice if the first one proves too challenging to do well.

This will be a multi-part process and may take 4-7 weeks of publishing to get through what I am able to cover. There will also be large pieces missing (I’ve done this before, but only for teaching and personal activity…expect some errors to be made). Feel free to comment if there is something you don’t understand. It may very well be an error on my part or explaining it better will help us both.

Just remember, the price (free) guarantees that you won’t overpay unless you find it a waste of time. Then…check back after the series is done.

It should be noted that expected return does not imply actual return. If that were the case, the investment would not be riskier. We should think of risk as variance. Note that this is not 100% true as we also need to consider the correlation, but we’re going to ignore that for now.

A perfect example of different skill sets as my artistic talent approaches that of someone in first grade (apologies to first graders everywhere). It probably would have taken about the same time to do this with software (and would have looked way better), but I’m too lazy to do that. So you get my lack of art skills. You’re welcome. 🤣

Great article

Howard Hughes please