Hindsight Bias, The Matthew Effect, and Randomness

How Much of What We KNOW is Real?

Hindsight Bias and What We KNOW

Let’s start with a quick review of hindsight bias, which is likely a familiar term in which the outcome appeared to be obvious AFTER we knew what happened. Our brains like stories and stories tend to have cause and effect. Once we know the effect, our brain will fill in the cause for us. In grading papers over the years, the number of times students “knew” a stock was going to be a winner was surprisingly high. Or at least that was what they wrote when reviewing their trades for the semester for a position that went up. There were also the mistakes in which they SHOULD have known that something bad was going to cause the stock price to drop. Unfortunately, reality is rarely as clean as the stories that get filled in by our brains when we try to make sense of what happened. It is only “obvious” in hindsight.

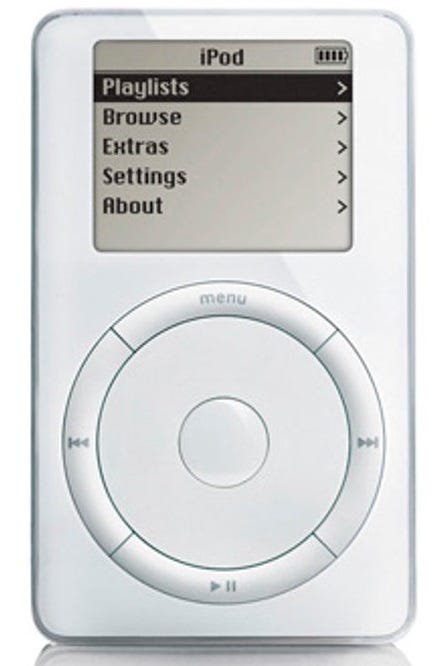

This leads us to a popular school of thought being played out now in many investment podcasts, articles, etc. which is essentially that if you would have just purchased Apple, Amazon, Bitcoin, Microsoft, etc. and held through the drawdowns, you would be very successful. This is all true, but also less helpful than one might think. The reason is that it is hard to separate out the good decision from the good result. This is especially true when you figure in the optionality. For example, when Apple took over the MP3 market with the iPod in late-2001, they set up their transition from a computer company to a consumer electronic company (officially changing their name from Apple Computers in 2007).

The iPod led to the iPod video to the iPhone, iPad, iTunes store, etc. And, along the way they became cool in the computer market again. How much of where Apple is today is due to the iPod? Obviously, they had to keep the innovation going, but would Apple be the most valuable company in the world without the iPod which enhanced their brand?

Reflexivity and The Matthew Effect

There is also reflexivity in which the initial success of a product or firm makes it more attractive, which helps fuel its continued success. As Tren Griffin comments, humans may be less independent than we’d like to think.

This does not imply that the success is not earned, but that it may have been gifted with an assist — the Matthew effect. The Matthew effect argues that early advantages, which may be real, perceived or a combination of both, create benefits that will compound. This compounding can often be rather dramatic. In a study looking at music popularity, Matthew J. Salganik, Peter Sheridan Dodds, and Duncan J. Watts found that the how much an individual liked a song was highly correlated to how popular the individual thought the song was. If they knew that others liked the song, they were more likely to rate it highly than if they had no idea how popular it was. Alternatively, if they knew that others did NOT like the song, the were more likely to rate it worse than if they were unaware of the popularity. In other words, how an individual felt about the song was dependent on how they thought others felt about the song.

Increasing the strength of social influence increased both inequality and unpredictability of success. Success was also only partly determined by quality: The best songs rarely did poorly, and the worst rarely did well, but any other result was possible.

Note that this dependency was not enough to make a bad song “good” or a good song “bad” to listeners. However, it was enough to influence the perceptions of the songs in the middle. A mediocre song could be determined to be either “good” or “bad” depending on the perceived preferences of others.

This phenomenon has shown up in multiple places, including bestselling books, reading success, sports, and other places. Think about Facebook (yes, I’m in the “olds” camp). Why is it one of the most popular social networks? Because everyone you know is there. Some of this is based on real underlying strengths of the company and some of it is based on the firm’s past success. However, there is an advantage to gaining an edge on your competitors, as that edge is more likely (although not guaranteed) to magnify than to shrink.

Separating Outcome from Process — Avoid Resulting

So, we have feedback loops, optionality, reflexivity and general randomness where we can only see the outcome. However, the outcome can be misleading. Consider the stories of Kevin Durant and Greg Oden. Durant has become one of the top players in the NBA and was drafted #2 behind Greg Oden. If you are not a hoops fan, you may not be familiar with Greg Oden, but he was a dominant college player at Ohio State. Unfortunately, knee issues cropped up almost immediately in his NBA career which led to him being regarded as a “bust”. Does that mean that Portland made a bad decision or did they get a bad outcome? Also, Seattle (who became the Oklahoma City Thunder) had a great outcome with Kevin Durant (at least for a few years until he left to go to play for the Golden State Warriors). Did they make a great decision? We don’t know. It is easy to engage in resulting and say the Portland made a bad decision while Seattle/Oklahoma City made a great one. However, that is largely the result of knowing the outcome. Annie Duke famously refers to this as resulting. Imagine a coin-flipping contest with 1024 participants. The goal is to see who flips the most heads in a row and let’s assume it is a 50/50 shot on heads or tails (is it really?) and the probabilities hold exactly. After one flip, half the participants will still be alive (512). After two flips, 256 participants will still be alive. On the 10th flip, we will have a winner who flipped 10 heads in a row. Is that person a good coin flipper?

Simulation

So, let’s do a little simulation.

We need to cheat a little bit and make some assumptions on a distribution. To keep it simple (too simple), assume a 10% mean return and 30% standard deviation and a lognormal distribution of monthly returns. However, for 500 “stocks”, we’ll assume they do worse than normal (an 8% mean return), while the other 500 do better (a 12% mean return).1 In 1000 trials over 3 years of returns, stock A outperforms stock B about 30-50% of the time despite the fact that someone investing $100 into a stock earning 8% would end up with $127.02 vs. $143.08 for the 12% return.2 Despite the “good” stock ending generating investment income of $43.08 vs $27.02 (an improvement of almost 60% in benefits) over the 3 years, a significant percentage of times the “bad” stock actually does better. Interestingly in my simulation, if we look at all 1000 simulations, my “low return stocks” generated an average value of about $145 while my “high return stocks” generated an average value of about $160. This is related to the skewness of the lognormal distribution (where outliers will tend towards the high side). If you use a normal distribution, the numbers come in closer to the $127 and $143 values. However, in that simulation, we still have the “low return stocks” winning 1/3 of the time in the top 100. Good decisions will generate bad results from time to time, just as bad decisions will occasionally generate good results. This is why we need to think of the underlying process, rather than just focus on the result.

Conclusion

Now, keep in mind that we don’t really KNOW the underlying average return and standard deviation of the underlying investment. We also aren’t incorporating momentum, optionality, etc.

The point of this post is not to say that Apple, Amazon, Facebook, Microsoft, Shopify, etc. are not good companies or good investments. They might be. For full disclosure, I own small positions in Amazon and Facebook plus likely have each of these in funds. Instead, it is to say that we need to be careful about classifying them as such. More importantly, don’t confuse a good company with a good investment without considering the price we are paying for that investment and what the potential outcomes may be (regardless of whether or not those outcomes are realized).

Consider someone who bought Microsoft on the close of December 27, 1999 for a split and dividend adjusted price of $37.74. That individual would have been underwater on their investment until July 16, 2014. You could seriously question the financial acumen of someone in 2010 who argued that Microsoft was a good company. However, between the end of 1999 and 2014, Microsoft saw sales grow from about $20 billion to $87 billion and net income grew from about $8 billion to $22 billion. It is also easy to forget that some companies who were thought to be powerhouses in the late-1990’s (General Electric, Exxon, Cisco, etc.) have struggled tremendously since then (especially relative to the S&P).3 This concept was documented brilliantly by Warren Buffett in a recent Berkshire Hathaway annual meeting and in this graphic of largest companies over time (seriously, take a minute to view that link…it is a powerful indicator of how successful companies can drop off the list pretty quickly and new firms can emerge).

Note that we are actually looking at 500 trials with an 8% expected return (converted to monthly) and a 30% standard deviation (also converted to monthly). Then another 500 trials with a 12% expected return (converted to monthly) and a 30% standard deviation (converted to monthly) over 3 years. The initial “price” of the stock is $100. If you want, you can change any of these assumptions (note that the “price” is irrelevant as long as it is the same in all cases, because the return is what drives the price change). For reference, here are some standard deviations since October 2019 — Tesla 75%, Facebook (Meta) 34%, Netflix 33%, Microsoft 25%, Moderna 98%, Google (Alphabet) 27%, and Amazon 29%.

In the included example, the “low” returning stock actually did exceptionally well by “winning” 44% of the samples.

Specifically, the S&P 500 as measured by the SPY ETF has generated a cumulative return of 369% since the end of 1999 (including dividends). General Electric had a cumulative return of -52% over that time period, while Cisco and Exxon did better with cumulative returns of 42% and 211%. Note that both GE and Exxon took turns as the largest company in the US over this time frame.