College -- Part Two

Once More Into The Fray!

Thanks to the New Subscribers

Apparently there are two new factors that have led to quite a few new subscribers to this little pond of the Interwebz that I take up space writing my, (mostly) weekly, thoughts on different topics. One is recommendations — an incredible tool by Substack to promote fellow writers. The other is a specific mention by the author of Moontower (honestly, I didn’t even have to pay him 🤣). Thanks @KrisAbdelmessih. Anyway, I’m now over 200 subscribers, so thanks to the new and the old subscribers for getting an occasional email that allows me to chat about different things that I enjoy. Please feel free to share any of these posts that you enjoyed.

Also, if any new subscribers want to share a bit of their story, I’ve done a couple of interviews with former students. Here’s one with Khalen Dwyer and one with Trevor Johnson. These are a great way to introduce me to some new people and I can learn more about their (or should I say your) successful journies. Plus, they are relatively easy to put together because you’re doing the work (laziness can be an attractive trait!). If you’d be interested, just let me know.

No Update Next Week

This is the first day of chemo (month 3…only 9 more to go once this is done!) and I can feel the sleepiness kicking in already. Some of the new subscribers are thinking “Wait a minute, we’re reading stuff from a guy with hole in his head?” Yes, a case of oligodendroglioma — say that three times fast — had me on the operating table on Christmas day (what’d you do on Christmas?). Fortunately, they think it was there for awhile, so apparently we’ve gone a few years without signs…make of that what you will. 🤣 Anyway, it’s being treated now and looks like I’ll recover fine (no comments from the peanut gallery). We’re going to take next week off and then I should be back the following week. Thanks for putting up with a bit of a hectic schedule.

What Is the Future of College — and Does It Have Room for Men?

Freakonomics took a week off to revisit abortion (yes, there ARE topics that are even too controversial for me to touch!) and then came back with episode four of college (the final one). If you missed last week’s episode, please hop back and read that first. I debated whether or not to include it and decided it was worth covering as it addresses a pretty relevant topic — are we leaving young men out of the educational experience — along with an intriguing look at the connection between student-faculty-employer and certificate programs. So, we’re back to college for one more round. Here Stephen Dubner introduces the topic (and a huge shout-out to Stephen Dubner for all he does with Freakonomics and such…really, consider taking the time to subscribe/listen to the episodes as it is well worth it!)

What is the long run for higher education in the U.S.? If we were asking that question 10 or 15 years ago, the answer would have been easy: “Things are looking up,” we would have said. Enrollment is up. Investment is up. Belief is up — belief that college is easily the best route to achieving the American Dream. But today, it’s a different answer. For the first time in modern history, overall college enrollment is down. Belief is down. And if you’re a college graduate looking at the size of your student loans, you’re probably feeling down too. This is the final episode in a series we’re calling “Freakonomics Radio Goes Back to School.” So far, we’ve told you how American higher education has two distinct models.

Ruth SIMMONS: One model is about eliminating people so that there is a special class of achievers at the highest end. The other model is about making sure everybody gets through.

We told you how that first model, the elite model, has been accumulating ever-more resources while educating an ever-smaller share of U.S. students.

Morty SCHAPIRO: Educating a very small sliver of the American population who already get tremendous resources allocated to them.

Those elite universities are generally thriving; demand for admission has never been higher. But what about everybody else? What about the less-prestigious privates; what about the four-year publics; what about the community colleges and trade schools, the H.B.C.U.s? Today on Freakonomics Radio, we take a look at this second model of higher ed., and why for so many people it is no longer working.

Donald RUFF: To see $100,000 as a debt burden is daunting.

We look at why men in particular are skipping college.

Amalia MILLER: Typical boy behavior doesn’t fit as well with good student behavior.

And we find out if the Lewis College of Business can make a comeback.

EDWARDS: All we did was borrow from nursing schools and welding schools and electrical schools.

Do you still believe in college? We’ll find out, starting right now.

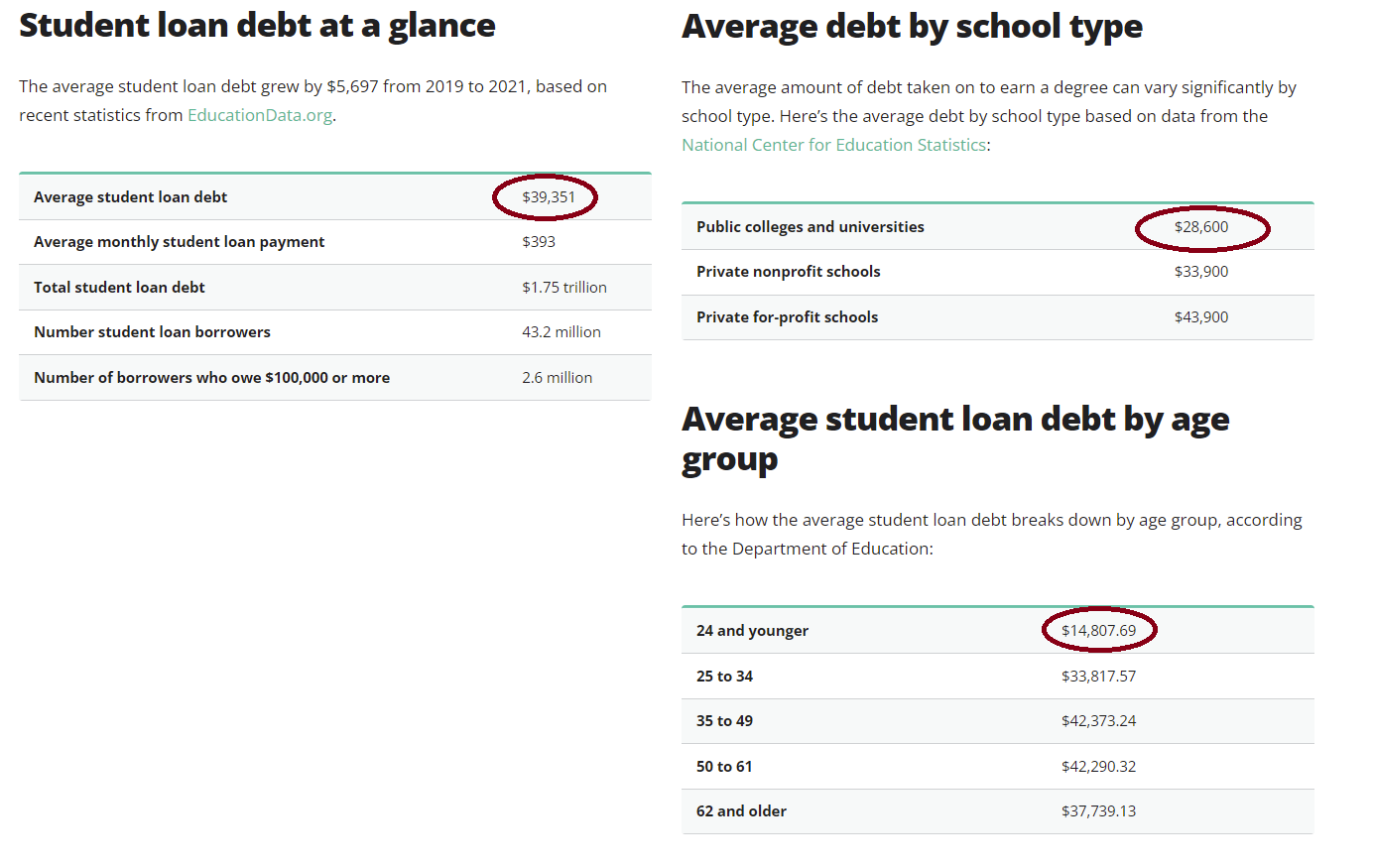

Let’s start with the debt burden which is (a) really high and intimidating, but also (b) not valid. Again, let me review the debt situation of college students from Credible.com.

The editing makes the pictures a bit hard to see, but I want to stress some things. First, the average student loan debt is $39,351. However, that is misleading as it includes graduate school, law school, medical school, and MBA programs which are significantly more expensive. Also, if we look at students who go to public schools (including graduate programs) the average debt load is under $28,600…we’ve now dropped the cost from $100,000 to $28,600. Finally, if we look at undergrads (granted, non-traditional students extend that, but they account for a small proportion of undergrads), we see that student loan debt is under $15,000 (yes, that does include community college so may be a bit too low). However, I think we can all agree that $15,000 - $28,600 is a LOT less than $100,000!

Again, this is one of those things that colleges NEED to do a better job of communicating. College is not cheap, but the idea of $100,000 in debt is also an example of poor financial decision making. Let me review Pittsburg State Universities tuition (and a reminder that I disagree with including room/board as part of college expenses) as an example.

Note that even if you DO include living expenses of over $1000 a month, you are not going to spend $100,000 on 4 years of college before we factor in financial aid. If you don’t include that, you are looking at $40,000 in total costs with NO financial aid. We can debate whether or not that is too expensive, but using student loans as a proxy for cost is not a legitimate proxy! We need to shift the focus to actual cost less scholarships, Pell grants, and other forms of financial aid that does not need to be repaid. Then we can talk about whether or not college is too expensive (which is an open question).

Shift in Demographics

One point that Stephen Dubner explores is the shift toward’s more women in the college classroom.

But here’s a number that certainly surprised me: Nearly 60 percent of all college students today are women. That’s an all-time high. And remember what we told you earlier, that U.S. colleges and universities have lost about 1.5 million students in the past several years? Well, men accounted for 71 percent of that loss.

Those are some pretty staggering numbers! Both the number of women and the declining enrollment of men. Dubner (and co-hosts) offer a number of potential explanations:

Start a football team? I think this was meant as a joke, but not 100% sure.

Demographics and workforce shifts. This is presented in a couple of different ways. First, there were 250 women’s colleges and now it is about 30. Also, the GI Bill caused a big shift of women coming back to college (which actually flipped the ratio to 2-1 men). However, it has now switched back to 60% women.

Economic factors. This is actually my favorite explanation as it ties to rational behavior.

First, there has been a shift towards more women entering the workforce over the past 30 years. This typically (again, not always) leads to better opportunities for your career (and gets more women into decision-making authority).

Second, the relative gains for women are more substantial because they are starting from a lower entry point (part time, retail, etc.) which creates a greater potential gain.

That’s Amalia Miller. She is an economist at the University of Virginia.

MILLER: Why might more women choose to go to college than men? As an economist, the way you think about it is thinking about the net benefits, the costs and benefits of that decision. So, the benefit side of college could be the earnings you get as a college graduate, where the cost side is the earnings you don’t get, that you would have gotten. And it could be that that’s higher for women than for men. If you think about some of the non-college jobs in the service sector that women are concentrated in, these are some really low-paying jobs. Blue-collar occupations or jobs that paid a decent wage that didn’t require college, a lot of those were more male-dominated.

In other words, a man who doesn’t go to college might get a job in construction that pays well, whereas a woman who doesn’t go to college would be more likely to work in retail or perhaps as a home-health aide.

MILLER: It could be that even if college women earn less than college men, it was still more worth it for women because that gender gap was smaller. I think the problem with that explanation, though, is it doesn’t explain the increase for women compared to men in recent decades, where it doesn’t seem like blue-collar work has had great growth in terms of number of jobs or wages.

and

Miller and her co-authors found another significant result.

MILLER: What we find is that there’s a significant decline in women’s likelihood of being married in their late 30s if they attended a more elite school for college. If we think of marriage as a positive outcome, then this might suggest a bad outcome. On the one hand, there is this career advancement, but it happens at the expense of family formation. These women are less likely to marry, but when they do marry, they’re marrying men who are more educated.

Minority and Low-Income Students

I was fortunate when it came time to go to college as my parents were supportive of the experience and paid all expenses for the first four years!1 It is a lot harder for students without these opportunities. Whether they are low income or minority students, there can be more challenges in the way. One of the biggest is just recognizing that college IS a potential outcome and that there are ways to make this happen (such as Pell grants, needs-based financial aid, work-study, etc.). As a high school student, I KNEW that I would be going to college and was able to take classes to help prepare me for that experience. However, those opportunities are rarely there for kids with single parents, financial struggles, bad living environments, etc. (and I say this in generality…some of these students have tremendous drive, mentors, parents that refuse to let them slide, etc.). Consider the case of Donald Ruff. He is the interim C.E.O. of the Eagle Academy Foundation.

They operate five college-prep schools in New York City and one in Newark, New Jersey.

RUFF: Honestly, we saw what was happening in our communities with the young men in particular, not just the graduation rates, the high incarceration rates, as well as the influences of some of the more negative elements, including gangs.

Their New York schools are part of the city’s Department of Education — which happens to be run by the Eagle Academy’s former C.E.O., David Banks. But as Donald Ruff tells us, his schools are different from the standard public school.

RUFF: One of the things that we wanted to do is actually create a school and a culture where young men could feel safe, where young men can authentically just be themselves, be boys.

Another big priority is making sure their graduates get into college. In New York City, nearly 60 percent of all public-school students go straight to college. But that number is much lower for Black and Hispanic students, in New York and elsewhere.

RUFF: Just going back to 2019 as an example, the college enrollment rate was about 37 percent for Black students, 36 percent for Hispanic students, and 41 percent for white young men. And at that time, our enrollment rate was at 73 percent.

and

A college graduate is much more likely to be employed than someone who doesn’t go to college, and they earn more too. That said, there’s no guarantee, especially these days. Around 40 percent of recent college graduates are technically “underemployed,” meaning they have a job that doesn’t even require a degree — which also means it probably doesn’t pay very well.

This illustrates some of the challenges faced by minority and/or lower-income students who face challenges that a lot of students don’t have to worry about. Three quick comments.

They mentioned that the pandemic affected students. This is true. The pandemic impacted EVERYTHING! Online education works for a relatively small portion of the population (more on this in a minute), but not the majority of them.

Second, he mentions the $100,000 in student loans which is NOT reasonable unless you are using it to pay for every expense encountered over four years and not supplementing your income with any financial aid (most low-income, minority students are going to exhibit financial need).

Third, there are underemployed people graduating from college (just as there are underemployed people graduating from high school). I’ve had students that decided to become moms (or dads…but more moms). I’ve had students that took my business finance class three times or graduated with the mimimum required GPA. Maybe not 40%, but easily 20% would fall in the category of people going to college for reasons other preparing for a career.

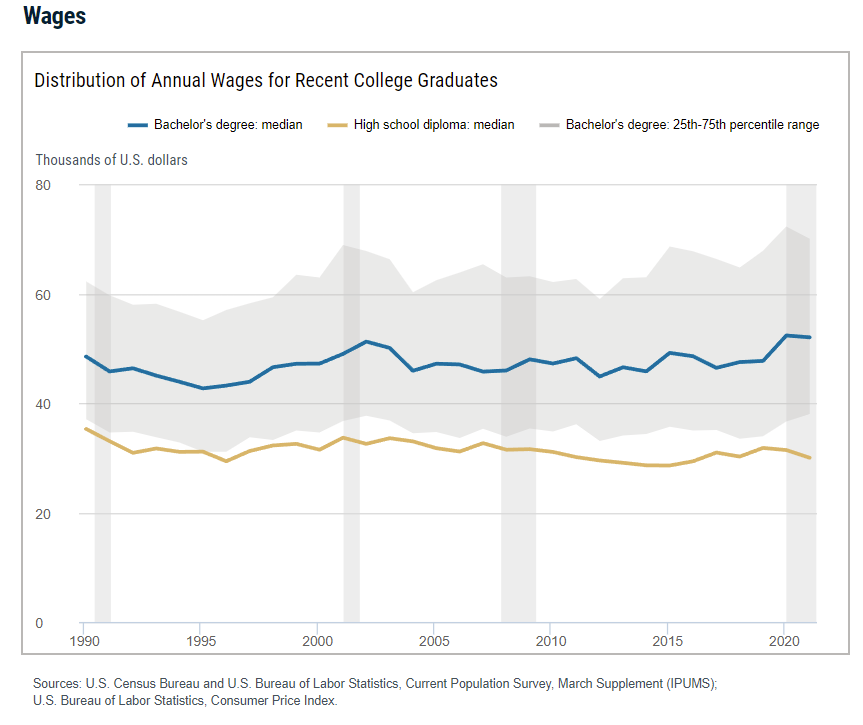

That said, consider this graph which shows the average wage for a college graduate ($52,000) vs. the high school graduate ($30,000). While these are NOT the same students (and an interesting debate about how much of the $22,000 per year is attributable to college would be an interesting question), I think seeing the cost of college around $40,000 and the net difference in salary of $22,000 per year makes college a worthwhile Net Present Value investment (see, even got a bit of finance in here 🤣).

Online Doesn’t Work

One of my revelations in teaching is just how poor of a tool online education is. There are things that I’ve been wrong about before, but this is probably one of the biggest. My initial view was that online education would wipe out traditional teaching. Feel free to stop laughing sometime in the next few minutes. It didn’t…at all. Here is a discussion from this week’s Freakonomics:

Teaching students online, however — that was supposed to solve this problem. It was scalable, it was efficient, it was cheap — it was perfect! There was just one thing: most people don’t like it. The best evidence for this was the Covid-19 shutdown.

Pano KANELOS: The whole world went online, and education went online, and we learned fundamentally that it just doesn’t work.

That is Pano Kanelos, who used to be president of St. John’s College in Annapolis, Maryland.

KANELOS: Online education just doesn’t work, whether it’s for K-through-12 or in higher education.

That may be an overstatement — but there is evidence that online schooling doesn’t do what its boosters said it would. Some research has shown that students who go to class in-person do better on several dimensions than the ones who study online: The in-person students get better grades, they’re more likely to do the follow-up coursework, and they’re more likely to graduate. And some of these are randomized studies, so they’re not just measuring the differences between the kind of students who choose in-person attendance over online.

So, nope. At least as of now, online isn’t the answer. Maybe in a few years with refinements, it will be. However the current model works well for a handful of busy, dedicated students. It works awfully for most students. We just aren’t wired to put in the necessary time to learn what we need to know (which varies tremendously between a nursing student, a finance major, and a graphic design artist) in order to enhance our ability to perform. I’m not sure if it is the student-student interaction or the student-professor (or teacher) interaction, or the entire college experience (my money is on the entire college experience). However, something is missing.

Certifications and Credentialing

This is an interesting concept and would work great for the right students. We did a little experimenting with Certification programs at Pitt State and I think it was headed in the right direction, but there was still some work to be done. First, here is an overview with D’Wayne Edwards

What about all the other students, and potential students, who are looking for a more practical college experience? What if there was a place that combined a traditional college environment with a practical certification program — and what if the education was free?

EDWARDS: I didn’t go to college. There was no money. No money for me to go to college.

That again is D’Wayne Edwards, whom we met at the start of this episode. He lives in Detroit now but grew up in Los Angeles, the youngest of six kids raised by a single mom. He’d always been a talented artist, and he loved designing sneakers.

EDWARDS: I discovered kind of late in my senior year I wanted to be a designer. And I didn’t know that you needed a portfolio. My guidance counselor didn’t know that. She actually discouraged me from being a designer, telling me that no Black kid from Inglewood would ever design shoes for a living.

DUBNER: As someone who grew up without college as an option, if you had not had this drive and talent for designing sneakers, what do you think you would have wound up doing?

EDWARDS: In Inglewood? Eighteen is a win if I can get there, alive or not in jail. Twenty-one? A miracle if I’m not dead or in jail. I have some friends that are not here anymore. I have some friends that are just getting out. That’s just part of growing up.

But thanks to his talent, and with the help of some teachers, Edwards took a different path. He went on to become one of the top shoe designers in the country. He spent many years at Nike, working with Michael Jordan and Carmelo Anthony; he got more than 50 design patents.

It’s important to note that while the benefits of college go well beyond learning a trade or skill, there are students that financially, mentally, and for a hundred other reasons don’t really need four years of college, but might be ready in one or two years (or even a few weeks) of focused training. D’Wayne focused on developing a shoe design program that lasted two weeks — “It was 14 days, 12 to 14 hours every day, straight through. We didn’t take a break. And the kids loved it. They didn’t want to leave.” Why? They loved this because it was what they wanted to do. They were working with someone who was well respected and it didn’t distract them with information that they didn’t care about.2

So Edwards taught professionalism.

EDWARDS: Simple things. Show up at 9:00 — 8:45 is on time. If you’re late, you do 50 pushups per minute.

DUBNER: Get out of here! At school?

EDWARDS: At school. And then it got to a point where the kids were like, “This is not fair.” So they were like, “Well, what about other options?” Actually a really good idea came from one of our employees, who was a former student. He was like, “You should make the students before the final presentation explain to the brand how often they were late and how many minutes they were late.” So now they have a choice —

DUBNER: Push ups —

EDWARDS: — Or you admit your flaws to the person that’s trying to hire you.

This is another area that a lot of schools are starting to offer — courses on professionalism. Things like showing up on time, table manners at a business lunch, working with others, etc. These are more important skills than many people realize. Grow up in the right environment and you learn it through osmosis.3 Grow up in a different environment and you probably won’t. Despite common perception, the average 22-year-old brain is not the same as the average 35-year-old brain.

Edwards doesn’t see himself as any sort of college revolutionary. He sees himself as someone who realized that college has become too expensive, too inaccessible, and too divorced from its original goals — and then he found a way to do something about it.

One key disclaimer is that these types of programs are not designed for students that want the full 4-year college experience. Instead, they are designed for programs that require specific training in conjunction with the industries that hire those students. It is a great model for the right student, but it is a piece of the overall model instead of a replacement.

Wrap Up

So, let’s go back to the question asked at the beginning of the article: “Do you still believe in college?”

My answer is definitely yes! That said, it’s a system that needs some changes. There is room for elite colleges, but as the numbers indicate, most students go elsewhere. As Stephen Dubner states

Fewer than 10 percent of them go to one of the elite schools at the top of the pyramid. The majority attend what are called mid-tier public or private four-year schools. About 25 percent attend a community college or other two-year school — although nearly half of all students start out at a two-year school. And nearly 10 percent go to for-profit colleges. Of the total undergraduate population, around 53 percent are non-Hispanic white, while 21 percent are Hispanic, around 15 percent are Black, and just under 8 percent are Asian.

So, let’s focus on state schools, regional schools, community colleges (although less as feeder schools and more as certificate/credential schools) and other programs. If a student starts at a community college and decides that they’d rather move to a four-year program, that is great. However, the sooner that they move to a four-year school, the better their college experience is likely to be.

Let’s spend more time working on online education. There is something there, but the current model doesn’t work. Maybe it won’t work. Maybe it will. However, the version being offered now doesn’t appear to be a valid model. One potential reason could be that we are still educating kids whose brains don’t fully develop until they are around 25-years old. While some are motivated (narrator — he was not one of them), most are not. Having faculty who care about the development of their students is not only important, but essential. Getting that student-faculty AND student-student connection into the curriculum is critical to success.

One last thought. Don’t confuse success of the student with success of the school. Every college graduates great students who would have been just as successful without college. Every college also graduates students who probably learned very little beyond how to party. These are the outliers. The more important part of college is how well we do at educating the average student with reasonable motivation. They may take a day off here and there. They may take not prepare for every exam or projects may not represent their best work, but overall they are learning from interactions with those that make up the college (other students, faculty, staff, etc.). They may have entered college with no idea what they wanted to do. I went to Iowa State for one semester to be a mechanical engineer before transferring to Northern Iowa as an economics major. I then “discovered” the stock market in my sophomore year with goal of only buying stocks that would go up (this would be funnier if it wasn’t true). It wasn’t until my junior year that I realized my future would have to do with finance and my senior year that one of my professor’s mentioned the possibility of a PhD that my career path became somewhat clear.4

So, do you have a story of YOUR college experience you’d like to share? If so, send me an email (kevinbracker@gmail.com) or leave some feedback to share YOUR story! Am I on track with my suggestions? Am I missing something (the answer is YES, but what am I missing)? Share your college experience and offer some feedback!

Thanks Mom and Dad!!

Note that I’m not saying that they shouldn’t have cared about it, but the reality is that between learning essential job skills with other highly-motivated students, they may have been a little less concerned about the quadratic formula. It makes a lot of sense.

No, you don’t really learn it through osmosis, but due to being raised in an environment where it pays off. However, we need to remember that not all students come from a traditional family and aren’t exposed to the same things as everyone else.

That’s a story in and of itself as we drove to New Orleans to tour Tulane University.