I’m Back!

Okay, I didn’t really get “pulled” back in, but decided my sabbatical had run it’s course so more of a case of jumping back in. However, I like the quote, so…

I’ll probably be a bit more sporadic this time around, so be warned that your schedule will be less predictable. No more regular 2:00 AM (CST) updates on Wednesday morning, but instead they’ll get out when they get out.

Three Free Liberty’s Highlights One-Month Trials

Again, you know you want to read Liberty’s Highlights and the cost is FREE! There are three free one-month trials out there for you to claim (donated by LibertyRPF himself — Thank You!!). Even if you’ve already won, enter again by sending me an email or reply to this forum. The FIRST THREE responses will win. You’re not under an obligation to subscribe, but I think after you see 12 episodes, you’ll want to expand that to a full year and join me and others as paid fans.

Range Widely

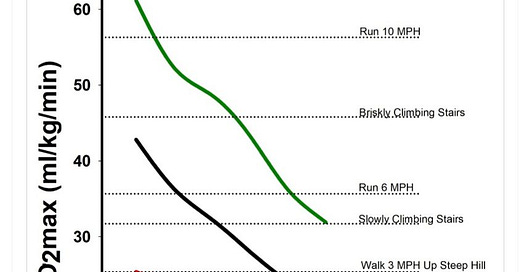

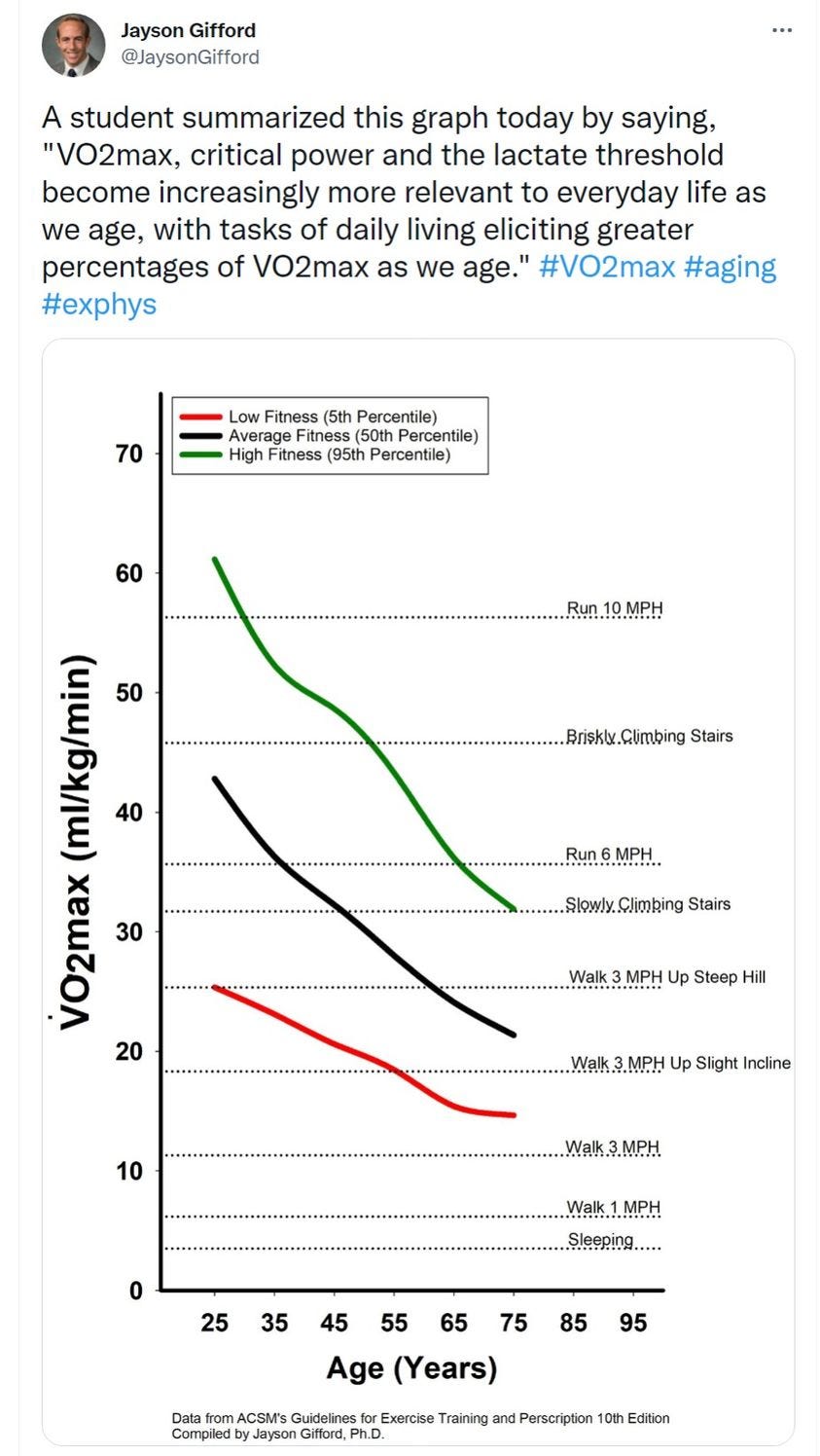

I’m sure I’ve mentioned David Epstein’s Range Widely column before, but he had a recent column that is worth another look. Here is his column on running and why it is good for you regardless of gender. One of my favorite takes from this column is this one

WOW! I don’t necessarily want to live longer (well, actually I do as long as I’m still mostly functional), but I want my (reasonably) healthy years to be as long as possible. This is a great argument for staying fit. Side note is that it doesn’t matter if you run, lift weights, walk, crossfit, backpack or whatever keeps you active. The better your VO2max is, the more likely you are to have more functional years in there. Obviously, randomness is going to play a big part…and there’s not much we can do to manipulate that lever. However, working to stay fit is likely going to be a major factor on our ability to stay functional as we age and I’m all for that.

A Return To Higher Education

A recent tweet caught my attention as it looks at one of the challenges facing higher education — how do we make it more functional for those involved? You can find the story here (and note that you are receiving a piece of the story…not the full picture because each person is going to experience it a bit differently).

Essentially, it is a question about whether the class itself is too hard or the students are not putting in the appropriate amount of effort…or, most likely, a little bit of both.

Let’s introduce the story a bit and then delve deeper into the details. Dr. Maitland Jones, Jr. teaches a section of organic chemistry at NYU. Depending on who you talk to, he was either one of the coolest

He received awards for his teaching, as well as recognition as one of N.Y.U.’s coolest professors.

or most dismissive faculty members on campus.

But Mr. Beckman defended the decision, saying that Dr. Jones had been the target of multiple student complaints about his “dismissiveness, unresponsiveness, condescension and opacity about grading.”

Dr. Jones’s course evaluations, he added, “were by far the worst, not only among members of the chemistry department, but among all the university’s undergraduate science courses.

The truth is that he was probably both. Side note — I’ve had students tell me that I was their favorite professor on campus AND students tell me that I was their least favorite professor on campus.1 Teach a broad enough sample of students and you will hit both extremes.

Who is Your Customer — The Student or Society?

One of the challenges of teaching is trying to figure out who your “customer” is. For many industries, this is relatively easy. Unfortunately, this is not true for higher education. You actually have multiple possible answers.

There is the student who is actually taking the class. They are the one deciding what to major in, which instructor to take, whether to take the class online or in-person, etc. The challenge is trying to figure out what they want from the course. Is it an easy A (or a passing grade)?2 A class where they memorize the material? A class where they learn to understand the material and how to apply it? There is definitely an argument that they are your customer, but if so, what strategy do you offer to make the customer happy?

There is also the parent(s) who may (or may not) be helping to finance the student’s education and wants their kid to be successful. While there is a lot of variance, parents are probably less concerned about the “party” atmosphere of campus. They are going to want career paths that are going to be rewarding for their kids (both financially and personally). When it comes to an art class or a STEM class, parents (again, on average) are going to want their kids to choose STEM-oriented careers.3 Specifically, this Forbes article argues that "A majority (65%) of respondents today work in the field their parents wanted for them." That’s a pretty strong number!

Another potential customer would be the businesses that hire the students. They are going to want students who understand the concepts and how to apply them. They are also going to want grades. Given the choice of hiring a student with a GPA of 2.5 or a student with a GPA of 3.8, most businesses are going to go for the student with the 3.8 GPA. The GPA is a “signal” of how well the student is doing at processing information, completing assignments, balancing multiple deadlines across classes, working in teams, etc. These are proxies for the skill sets that employers are looking for from their new hires.

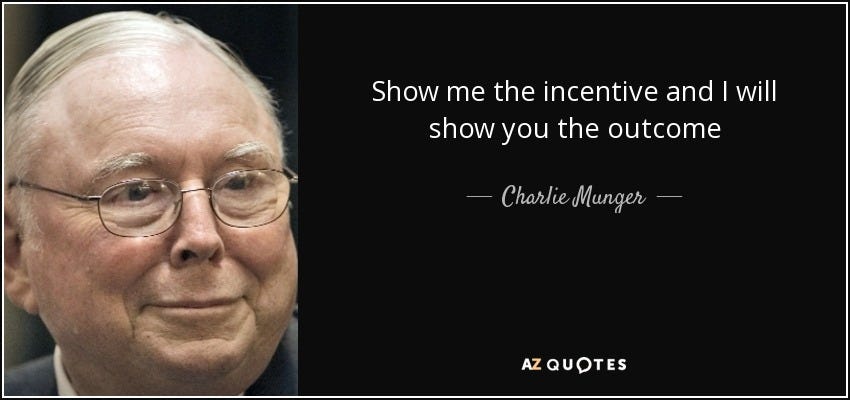

Going back to the student that wanted the easy A, you can start to see the problem. Getting a B in a class and learning the material is less beneficial to the student than getting an A in the class. It is going to impact scholarships, interview opportunities, and allow more time to pursue current job opportunities and/or extracurricular activities that will help them get their career path started in the right direction. As Charlie Munger says

Another potential customer is university oversight. These refer to the many different regulatory organizations that provide a review of the university's performance. Three examples off the top of my head (for our school) include the Kansas Board of Regents, Higher Learning Commission, and AACSB (there are many more). The purpose of these institutions is to ensure that learning is occuring within appropriate guidelines.4 However, there is an issue with answering to too many bosses that can wear down teachers. You spend more time doing paper work (or filling out online forms) and attending meetings which distracts from the time you have to develop classes and interact with your students.

There are benefits to rubrics in that they tell students how the project is going to be graded.5 This is great as they know what is expected and help keep professors honest in their grading.6 However, if they start doing the project BASED on the rubric, they are maximizing their grade and quite often are no longer focusing on what they should be LEARNING from the project. Focusing on oversight of education is likely to create as many problems as it fixes. However, there is a big difference between faculty teaching because they have a passion for doing it vs. faculty teaching because they are obligated to so.

So, who is your customer? They each have different objectives and optimizing for any one of them is not going to be optimal for the others.

The best instructors try to envision where the student is going to be after they graduate and create lectures to help them get there.7 This is true across campus, regardless of whether they were teaching finance, business law, photography, nursing, or mathematics. Teaching how to think is much harder to grade (for one, it assumes instructors know how to think which was always up for debate in my classes). You are grading the thought process rather than the ability to spit out a formula and apply the formula correctly. Ideally, you are doing both -- grading the ability to apply the formula WITH the ability to understand and apply what you just calculated.

If I ask you to estimate the future value of $1000 PER YEAR saved for 40 years at 12%, are you going to give me a number of less than $40,000 (this occured every year in Investments II), a number between $40,000 and $100,000, a number between $100,000 and $1,000,000 or a number greater than $1,000,000? Note that if you do the calculation, you will get an answer of $767,091. When asked to provide an estimated range, that would give them a 75% chance of getting the correct answer within that range, the results were often discouraging.8 In 2019, I had about 9% of students get the range right (note that someone who said between $100,000 and $1,000,000 would be right whereas someone who said between $200,000 - $400,000 would be wrong). The number of "correct" responses would vary from year to year, but never exceeded 25% (and often was far less than that).

Granted, we expect the “confidence” in our answers to be too high, but it always amazed me the number of guesses that were not close. There were multiple reasons for this (end of semester, students not wanting to spend time thinking, people who guessed $500,000 - $700,000, etc.), but the reality is that students who had spent the last year doing literally hundreds of time value of money problems, struggled to get the right answer (fortunately, they did these problems across other classes, so I was only partially to blame and it was the expected outcome). Still…

Back to the Story

Let’s get back to the story itself where NYU terminated the class of an adjunct professor due to student performance. It is open to debate whether the class was too hard or the student’s too soft (I’m going with it was a bit of both). The initial solution was

The officials also had tried to placate the students by offering to review their grades and allowing them to withdraw from the class retroactively.

It wasn’t exactly the passing grade that they needed, but it also wasn’t going to damage their GPA. As the school described Marc A. Walters, director of undergraduate studies in the chemistry department as saying

the plan would “extend a gentle but firm hand to the students and those who pay the tuition bills,” an apparent reference to parents.

As the article states,

Should universities ease pressure on students, many of whom are still coping with the pandemic’s effects on their mental health and schooling? How should universities respond to the increasing number of complaints by students against professors? Do students have too much power over contract faculty members, who do not have the protections of tenure?

This goes back to the question of who are you teaching to? The students and parents (at least of those doing poorly in the class, which is not all students) are going to be happier with this solution.

Dr. Jones responded with the following

The problem was exacerbated by the pandemic, he said. “In the last two years, they fell off a cliff,” he wrote. “We now see single digit scores and even zeros.”

After several years of Covid learning loss, the students not only didn’t study, they didn’t seem to know how to study, Dr. Jones said.

I can say that this was one of the issues that I saw in my classes as well. I’m not sure if it is more of an issue in degrees that have specific requirements — I need to complete requirement X with a grade of B or higher to move on to requirement Y — or not. However, my gut feel is that this IS part of the issue. These students are outcome-oriented learners. Rather than learning because they are interested in organic chemistry (or finance), they are interested in meeting the outcomes rather than learning the material (and again — this is not all students). I often speak of a range of students that used to be about 25% that really wanted to learn, 50% that would vary from day-to-day, and 25% that didn’t really care. However, since COVID and increased online education, I would say that the numbers dropped to about 15% that really wanted to learn, 35-50% that would vary from day-to-day and anywhere from 35-50% that didn’t really care as long as they got the grade that they wanted.

There is also a question of access to professors. If you are on campus, it is easy enough to stop by the professors office and ask for help. However, what if you are trying to learn from home? You may be studying at night and have a question. You email the professor who doesn’t see it until the next morning, has a meeting/class and get’s back to you in the afternoon. You don’t see the response until the evening. Instead of spending 5-10 minutes talking through the issue, you spent a day (or more) trying to get one question answered (and maybe still didn’t get what the instructor is trying to convey). This is going to cause a lot of undo stress due to time lags, equipment availability, nuance, etc. Now multiply that by 30 students!

Another issue is with communication and intent of the communication. Here we see the complaint from students

The students criticized Dr. Jones’s decision to reduce the number of midterm exams from three to two, flattening their chances to compensate for low grades. They said that he had tried to conceal course averages, did not offer extra credit and removed Zoom access to his lectures, even though some students had Covid. And, they said, he had a “condescending and demanding” tone.

Dr. Jones had responses for each of these (exam dates too early in the semester, lab scores which were not completed, etc.). Are both of these groups correct? Likely, yes. However, an interesting quote from his teaching assistant

I have noticed that many of the students who consistently complained about the class did not use the resources we afforded to them.

We also see that students were a bit unhappy with Dr. Jones attitude

Several of them said that Dr. Jones was keen to help students who asked questions, but that he could also be sarcastic and downbeat about the class’s poor performance.

This is one of the more challenging issues facing instructors. How do you use class performance which is underwhelming to motivate students to do better going forward? If you ignore it, they will assume that it is normal. If you address it poorly, you’ll harm yourself (been there, done that). The key is to say that you know performance was worse than expected and here is how we (both you and them) are going to improve it. Easier said than done, but an important tool in the instructors tool kit is to know how to be “disappointed” in the performance but “excited” about the opportunity for improvement. We are going to work harder going forward! This is a legitimate possibility (at least for some of the students).

One drawback is the perception of difficulty is being determined by students. As Nathaniel J. Traaseth (a chemistry professor) stated

“Now the faculty who are not tenured are looking at this case and thinking, ‘Wow, what if this happens to me and they don’t renew my contract?’”

Does this imply that we are going to see teaching standards stay difficult? Are instructors going to need more student-pleasing attitudes (aka better PR strategies without weakening demands)? Or are we going to make classes easier to appease angry students and parents? I know which path I’d rather see, but accomplishing it is hard. My former school has seen full-time equivalent enrollment drop by nearly 20% over the past five years (this is only one of the reasons)! Addressing this (and other challenging environments) are one of the many reasons that I would not want to be in the shoes of administrators that need to fix the problem. It’s Freakin’ HARD!

While we all think it’s better to focus on where the students will be throughout their life, it doesn’t solve the problem of who’s paying tuition today. I’m not sure what the best solution is, but know that higher education needs to figure it out before another 10+ years go by or the situation is going to get worse.

One of my favorite stories was the “gimme” question on the final to “tell me three things you learned this semester — explain the concept and why it was important to you.” One student took that as an opportunity to explain why my teaching style was atrocious. For the record, that was one item and explained well enough that she did get 4 out 10 points, but the question did ask for THREE items. I also won multiple teaching awards within the College of Business and one campus wide…which shows that as long as you’re in the pool for a long enough time period you’ve got a shot.

You may laugh at “a passing grade”, but the phrase “D is for diploma” was heard many times in the hallways or even directly from students. While that may have been a coping mechanism, there was also truth to it for many students who just needed to pass the class in order to graduate or knock of a pre-requisite course.

There is some evidence from David Epstein’s book “Range: Why Generalists Triumph in a Specialized World” that would argue that we may be better with more liberal arts type education instead of specialization.

You can argue whether or not these institutions are driving education in the right direction or not…and I don’t have an answer. Personally, I think that they are trying to accomplish this goal, but as with any large organization if you introduce rules and require people to follow them, you end up rewarding those that are politically adept at following rules rather than the ideas behind the rules.

If you aren’t familiar with a rubric, it is a system for assigning points on a project.

Keeping teachers honest in grading has almost nothing to do with the intention of the instructor. I never sat down to grade term papers with the intention of giving a B paper an A or an A paper a B. That said, it happened on a regular basis. I doubt if I ever gave a D paper an A (or vice-versa), but being off a letter grade was bound to happen due to what kind of mood I was in, whether it was the 1st or 10th paper I read in a row, the quality of the first page vs. the last page (hint — it’s better to start well), and several other factors. Any instructor that tells you otherwise is likely lying (either to you or themselves).

I may be showing my age, but am more comfortable using they/them rather than rotating randomly between him/her.

Note that this was a “behavioral” quiz designed to show that we do a bad job of estimating ranges. This is a concept discussed (again in David Epstein’s Range book) where Fermi estimation is introduced — the process of coming up with a reasonable estimate for a problem “off the top of your head” for a difficult process. The idea is that people drastically overestimate our ability to “guess” an answer and that the more knowledge we have about the problem the more narrow our band (which makes the guess even worse).

I am interested int the liberty highlights subscription!