Twitter Thread

A couple of weeks ago, this thread popped up on Twitter.

This was followed up by a response from Liberty.

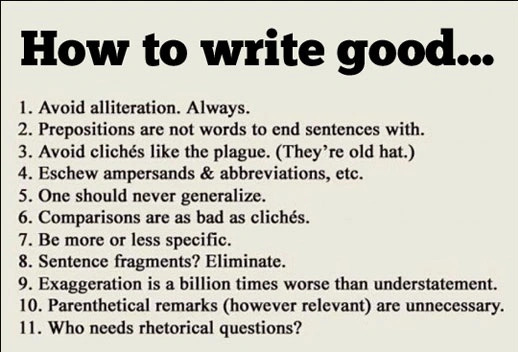

This drives home a couple of important components to writing. First, shockingly (narrator — no, it is not shocking at all), it is easier to read good writing than it is to produce it. If you’ve been reading my newsletter, this is probably obvious as I consider myself more of a competent writer than a good writer (yes, an easy “fishing for complements” spot, but that isn’t the point…the ability to move from competent to GOOD takes skill and practice). Second, good writing (non-fictional) draws the reader into a mindset that they are listening to someone tell a story. There are facts present, but the facts are presented in a manner that engages the reader in the story being told. Third, the arguments are laid out in a coherent manner. In other words, if there are pros and cons, both are presented instead of one. A really good writer acknowledges that there is nuance as things are rarely black and white, but draws you to his/her side of the story and supports that with actual data.

Breaking Down The Writing Process

Let’s start with 10-K Diver’s original post about creating a one-person show online….kinda like some guy wanting to write a mostly weekly Substack column.

Not Much Capital is Needed — This part is definitely true. Essentially, internet access and a word processor are all that are needed. Granted, there are other tools that are handy such as personality (you need to be promotional without being overtly promotional and outgoing) and connections (having connections to the right people can open a lot of doors). Someone like Bill Brewster definitely has the personality for it and it shows in his quality podcast. That said, the personality is a bonus and you can make the connections (thanks to social networks).

High Margins and Free Cash Flow — This is debatable. I’m guessing the vast majority of people trying to make their mark as writers don’t make much money. Instead, a few people do really well, but most of us are probably not making much. I’ve got a YouTube channel that over the last 28 days has 24,500 views and 1600 hours of views…which translates into $73.49 in ad revenue. Not exactly rolling in the free cash flow (on pace for about $900 on the year).

Scalability — This part is accurate and one of the great benefits of writing a Substack (or Review, etc.) column. The effort that I put together to write a column is the same as Liberty, 10-K Diver, Morgan Housel or any of the other guys…kind of. When I say kind of, it is because I’m guessing that they put more time and effort into it based on quality. However, the time that Morgan spends to write a column is not based on the time to write a piece for 100 readers or 100,000 readers. Instead, it is his ability that is both natural talent and, to a much greater extent, hard work.

Low Risk Chance to “Make it Big” — This is definitely true. But still potentially challenging. Making it big is a SIGNIFICANT accomplishment. However, keeping it big for a two plus years is much, much harder. You need to keep coming up with new material and stay fresh/relevant over time. It’s a TOUGH job!

Flexible Hours, Location, Etc. — Another benefit right there with “Not Much Capital is Needed". The internet and your computer can travel with you anywhere which can be a huge advantage for people writing about travel, restaurants, etc.

Now for the cons.

Super Heavy Competition — This is no joke. Want to start a newsletter on movies, general commentary, finance, virus-fighting technology, or any of 1001 other topics, you can take advantage of the low capital requirements and flexible hours/location to start one up. There are no barriers to competition which means you are competing against anyone with an idea(s) who is willing to put the time in. There are a limited number of hours in the day to spend reading (work, family, workouts, sleep…time is pretty scarce) and there are just under 8 billion people in the world. Granted, not everyone wants to write a newsletter, but if even 0.01% do, that gives you 800,000 competitors. Not exactly a low-competition market.

Newsletter Fatigue — Okay, I’ve written about 35 columns…and it is challenging coming up with new topics every week. The first few were easy. The last 20 have been harder. What happens when I get 70 columns in? Do I still have new information to write about or am I spent? What about someone who writes three times a week (like Liberty)? That’s a tall task!

Requires Consistently Creating High Quality Content — This is closely related to the second con. Writing is hard. It is relatively easy at first, but to keep writing new AND high quality content week after week is challenging. Coming up with new topics that are interesting to both me and my readers is hard, but also rewarding. That second part is important because I still enjoy the challenge of coming up with something to write about and put a positive spin on it. It is still fun (although remember that I still also consider running 100 miles to be fun, so there may be something wrong with my definition of “fun” 😀), but if I find myself struggling to write something for more than a month, it may be time for a break. That said, I’m retired and doing it for free which is far different than people who are trying to make a living off of this.

Liberty’s Response

By far the hardest thing is the consistency/discipline ONCE THE HONEYMOON PERIOD IS OVER.

This is definitely true. The honeymoon period is when you are writing new columns on topics that you’ve been wanting to write for years. However, that doesn’t last forever. Then you have to get into your writing mode and think of new stories to tell. The word “stories” there is important because that is a big part of bringing people into your world. Whether it is Donald Trump, Elon Musk, Warren Buffett, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, or hundreds of others they have the ability to make themselves part of the story they are telling (for better or worse). A story well told can beat all the facts in making a case because it is easy to relate to a good story. In Morgan Housel’s recent article on how people think, he mentions this quote:

George Packer echoes the same:

The most durable narratives are not the ones that stand up best to fact-checking. They’re the ones that address our deepest needs and desires.

Another part of Liberty’s comments are

Most fall into it as a way to get to somewhere else, so few people stick with it for a long time. Either they try to leave, or get good offers that pull them out.

This is a good point. I’ve only been following substacks for a year or two and I’ve seen several writers that decide to take a longer break or get called away into another career in equity analysis or some other area (and I imagine that is true in many other areas as well). Writing takes time. I probably spend about 5-15 hours a week on this column (now you’re thinking “really?”) and it doesn’t even look like it. It’s fun and gives me a way to scratch the “teaching jones” that I loved for quite awhile, so I enjoy the challenge, but it is time consuming.

A last line from Liberty

I think that what many people struggle with in any "business of one" is that everything is on you.

Feels good when it works, but nobody else to blame when it doesn't, or to support you when you want a break or life gets in the way.

Life gets in the way — you know, like brain cancer (which fortunately hasn’t impacted my writing 🤣). However, people like to take vacations, write bad columns (it is hard to bring your “A” game week-after-week), have kids that get sick, deal with personal issues, and the list goes on and on. Being the star is fun when it works, but it doesn’t work for anyone ALL the time.

Morgan Housel Can WRITE!

There are many good writers, but one of the best is Morgan Housel. If you want to read a great piece that he has written, you can do so here (and it is probably a worthwhile read as I plan to have a follow-up on it in the near future) — https://www.collaborativefund.com/blog/think/. Next week, we’ll come back to talk more about this blog itself. However, today I want to talk about the writing aspect.

One trait is saying things that some people won’t talk about. For example, if we look at Item #2, he mentions that

All of the information accessible on the internet is estimated at 40 trillion gigabytes, which is roughly enough to hold a high-def video lasting the entire 14 billion years since the big bang.

And that is just since the internet came online! First, that’s a LOT of information, but if we think of all the people in the world, that is about less than 2 years per person (remember that there are almost 8 billion people). So why is this something most people don’t want to talk about? Probably because it implies that we all have a little bit of crazy in us (some have a lot of crazy) that we don’t want leaking to the world. Most of our crazy is held in check due to our sanity FAR outweighing our tiny bit of crazy. However, think about one of his clarifiers:

As much as we know about how crazy, weird, talented, and insightful people can be, we are blind to perhaps 99.99999999% of it. The most prolific over-sharers disclose maybe a thousandth of one percent of what they’ve been through and what they’re thinking.

When you are keenly aware of your own struggles but blind to others’, it’s easy to assume you’re missing some skill or secret that others have. Sometimes that’s true. More often you’re just blind to how much everyone else is making it up as they go, one challenge at a time.

You know the guy that just walked the Pacific Crest Trail faster than anyone else (Timothy Olson in 51 days 16 hours and 55 minutes) or the guy that turned Tesla from a startup to a HUGE electronic vehicle company (Elon Musk). You’re not seeing every minute or thought of their life. They are choosing to share their success stories with you rather than the time that they thought their feet were going to fall off from the 1,000,000th step of walking a trail or the many times that they came close to going bankrupt. If they share a “danger point”, recognize that the reason they are sharing it is because they overcame that “danger point” and turned it into a success. You aren’t hearing from the guy that got picked off by a stray bullet in an action movie, but the one that overcame the odds to succeed which is going to look like a lot had to go right in order for her to accomplish the feat.

Another trait that Morgan Housel displays is his ability to use storytelling to make something feel real. An important part of this is to tell compelling stories which means that they are often quite real. Consider the story he tells here — https://www.collaborativefund.com/blog/the-three-sides-of-risk/. It is about how he survived an avalanche by not being there (more by chance than by planning). Take a few minutes to read it if you haven’t already done so.

Seriously, go read it!

Okay, I’m assuming you did (and just in case you didn’t, you should definitely make a point to read it soon). If you did, you are wrapped up in the story.

Earlier that month Tahoe received several feet of light, fluffy snow that comes from Arctic temperatures. The storm that hit in mid-February was different. It was warm – barely at the freezing point – and powerful, leaving three feet of heavy, wet snow on top of the light powder that came before it.

We didn’t think about it at the time – we didn’t think about much at age 17 – but the combination of heavy snow on top of fluffy snow creates textbook perfect avalanche conditions.

Imagine a thick layer of sand with a layer of heavy cement on top. Now imagine putting those layers on a steep hill. It’s fragile, prone to sliding down. That’s what Squaw Valley was like in late February 2001.

Do you feel like you are a part of that story? Can you see the foreshadowing of what was to come?

But if you’re skiing out of bounds – ducking under the DO NOT CROSS ropes to ski the forbidden terrain untouched by masses of Bay Area tourists – the system won’t help you.

Skiing out of bounds is illegal, a form of trespassing. The main reason resorts don’t want you doing it is because it’s dangerous.

It was tiny, not going over my knees. It wasn’t scary. I remember laughing. But the feeling is unforgettable. I didn’t hear or see the slide. I just suddenly realized my skis weren’t on the ground anymore – I was literally floating in a cloud of snow. You have no control in these situations, because rather than pushing back on the snow to gain traction with your skis, the snow is pushing you. The best you can do is keep your balance to remain upright. I remember putting my hands up and shouting, “Wahooo” like I was on a roller coaster. I essentially was.

There were three of them — Morgan, Brendan Allen and Bryan Richmond. Brendan and Bryan wanted one more run, but Morgan didn’t. So, he decided to meet them at the bottom of the run. Unfortunately, they never made it.

It’s been almost 20 years since this happened. Sometimes I think about everything that’s occurred since – college, marriage, career, kids – and remind myself that I’ve only experienced it because of a blind, thoughtless decision to decline another ski run.

And of course, he needs to tie it back to investments, so he adds this:

I don’t know if Brendan and Bryan’s death actually affected how I invest. But it opened my eyes to the idea that there are three distinct sides of risk:

The odds you will get hit.

The average consequences of getting hit.

The tail-end consequences of getting hit.

The first two are easy to grasp. It’s the third that’s hardest to learn, and can often only be learned through experience.

The point though is that if you read his story, which is incredible, you’ll see how well he brings you into the story. You are there with him and living these events alongside him. It is a tremendous talent.

The third part is presenting both sides and then either leaving the call to the reader or drawing the reader to your side. Both work, but the writer needs to mix them up depending on whether they are trying to let the reader decide or convince them. Let me go to his most recent column “Deep Roots”. The idea is that cause and effect are often more complicated than we realize as it is rarely one event that creates an outcome. Instead, it is a series of events. He makes a few arguments that show this and closes with the following passage.

The other is a wider imagination. The craziest events – good and bad – happened because little events, each of which was easy to ignore, compounded. Innovation in particular is hard to envision if you think of it happening all at once. When you think of it as tiny increments, where current innovations have roots planted decades ago, it’s more believable – and the range of possible outcomes of what we might be achievable explodes.

The key is that here he is trying to convince you that the results are often far more nuanced than we realize. It’s a strong point, but you need to bring the reader in with a story and then tell the story in a way that allows the reader to relate to your point.

Being a good writer is a bit of a gift as it takes a bit of talent to do well. It’s also one that’s taken a LOT of work on his part. He started working at Motley Fool after an aborted run at investment banking and wrote…a lot! Not to mention all the papers he wrote in high school and college. I imagine there are quite a few pages that have ended up on the floor as a result of working to be better.

One For The Road

Liberty just shared the following quote (which I found very insightful) about knowledge that has been something my wife and I have talked about off and on for the past year or so. This ties back in with my post on “Strange Coincidence” from a month or so ago. We WANT for the world to be a bit mysterious and unexplained, so having some “supernatural” phenomenon out there to do it appeals to our brains. We know something that other people don’t because it is a bit mystical and doesn’t fit our normal models…which is kinda cool! Unfortunately, it doesn’t make us smarter (at least in the traditional sense), but makes us more susceptible to being misled through gimmicks rather than knowledge. Granted “knowledge” changes (which is good!), but it is based on something real, observable, and repeatable.

🧠 🚩 Smart people can be more or less rational about different things. Nobody is equally rational about *everything*, but some people exhibit huge variation.

Someone whose day job it is to work at a hospital or in a research lab can sometimes come home and entertain beliefs that are incredibly unscientific.

It's a real thing, but it's not a good thing. To me it’s a red flag when people integrate their life and beliefs very badly.

Beliefs about different things may appear totally separate at first — like they belong to the “non-overlapping magisteria” that Stephen Jay Gould talked about — but everything is part of the same reality and the beliefs are outputs of the same brain.

If my surgeon tells me he's a major fan of astrology and lectures me about chemtrails, I'll suspect he's a bad surgeon and will seek out another.

and

That’s not to say that any of us are anywhere close to perfect — whatever ‘perfect’ means — but I think our goal should be to *aim* in the right direction, work to get better over time, and make sure we periodically examine long-held beliefs to make sure we’re holding them for good reasons and correct mistakes and that we’re at least aware of the possible flaws or alternatives (even if probabilistically and under uncertainty… as with everything).