Return

Where Does It Come From?

I have exciting news to share: You can now read Kevin’s Newsletter in the new Substack app (well, the 10 of you can 🤣) for iPhone.

With the app, you’ll have a dedicated Inbox for my Substack and any others you subscribe to. New posts will never get lost in your email filters, or stuck in spam. Longer posts will never cut-off by your email app. Comments and rich media will all work seamlessly. Overall, it’s a big upgrade to the reading experience.

The Substack app is currently available for iOS. If you don’t have an Apple device, you can join the Android waitlist here.

Honestmath on Returns

This is a great post (thanks HonestMath.com!) and provides an important insight into stock investing. There are essentially three ways to generate returns from stocks:

Dividends (and buybacks…but be careful with the latter)

Earnings growth

Changes in PE multiples.

You are essentially betting that the stock is going to “outperform” the market in one of these three areas (although they are not independent) and not underperform in one of the other two to offset your outperformance. So, let’s look at these three areas a bit.

Dividends and Buybacks

There are two primary ways in which companies can return cash flows to investors — dividends and buybacks. We need to be a little bit careful with both of these. One, dividend yields will often rise, right before the dividend is cut. There is a risk of high dividend yields being a market estimate that the dividend is no longer safe and has a higher than normal chance of being cut. Therefore, if you find a stock paying a 10% dividend in today’s market, it’s probably wise not to count on getting that 10% yield (doesn’t mean you won’t get it, but that it is far from a guaranteed return). Therefore, what you want to see are firms where the dividend being paid is only a portion of their FCF generation (note that this will be a high percentage for REITS as they are required to pay a lot out in dividends, but often will be far less than 100%). For example, consider Altria (MO) (which pays out about 7% of it’s stock price in dividends). Over the past 4 years, they’ve paid out $24.22 billion in dividends, but their FCFs have been $32.13 billion (about a 75% payout ratio). A company like Molson Coors Beverage (TAP) has paid out $1.05 billion in dividends over the past 4 years, but their FCFs have been $5.15 billion. Clearly, they are paying out lower dividends (7.0% vs. 2.9%), but that is because they have different structures. Other companies, like Alphabet (GOOGL) don’t pay out dividends at all, despite massive FCFs. Specifically, GOOGL paid out $0 in dividends on $163.7 billion in FCFs. The reason is funding growth opportunities. All else equal, (it never is, despite how often the phrase is used in academia) the higher the potential growth in FCFs, the more the company is going to want to keep to reinvest in itself.

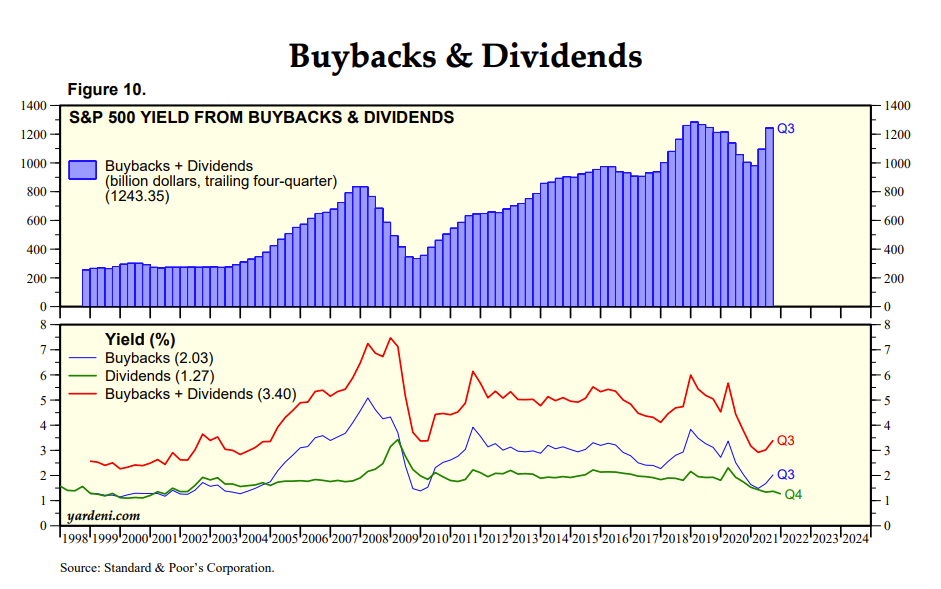

Another factor to consider is buybacks (when a company buys back it’s own shares). Here you can see a chart from Yardeni.com.

The green line represents the dividend yield and the blue line represents the buyback yield. Add them together and you get the total shareholder yield. Maybe. The reason I say maybe is that we really need to be looking at NET buybacks (buybacks less stock-based compensation). Stock-based compensation is a potential benefit in that it aligns employee interests with shareholder interests (they both make money when the stock price increases). This is good. However, it can turn into a bit of a sinkhole (see Twitter)

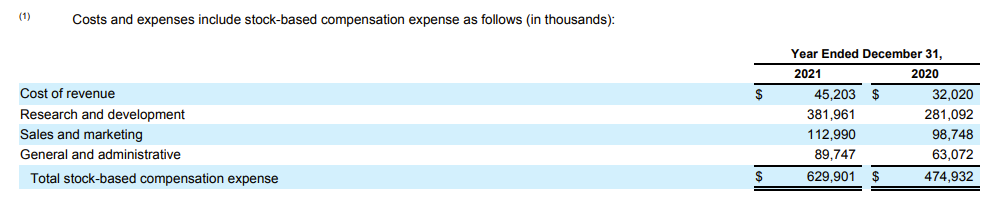

These numbers are in thousands, so that is nearly $630 million in 2021, up from $475 million in 2020. In both cases, that is over 10% of their total expenses each of the last two years. Now, if we look at repurchases, we see the following:

This graph illustrates two problems with buybacks. One is that they rarely pay attention to price paid. The second is that a lot of their purchases are given back to employees as compensation and the use of stock-based compensation can vary by sector. Check out this great article by Andrew Sather on SBC and the pros/cons. Here is a great excerpt from a very worthwhile article

So, we have a portion of the returns coming from dividends and buybacks, but you have to think about how reliable the return is going to be from each and how reliable it will be going forward. Ideally, you want to find a situation where the return from dividends/buybacks exceeds the market consensus for that particular stock. If not, you’re going to have to find opportunities from earnings growth or changes in the PE multiple.

Earnings Growth

Let’s assume that I have a stock that will pay out a dividend of exactly $3.00 one year from today and is growing at exactly 3% per year forever. Now, assume that my required return is exactly 10%. Are these numbers a bit ridiculous? Sure they are (what company grows by exactly 3% each and every year?), but bear with me for a minute. In this case, the stock is worth exactly $42.86 today. This is based on the Gordon Growth Model which says that the value of the stock is equal to next year’s dividend divided by the required return less the growth rate (P = D1/(k-g)). This works well in a hypothetical world where firms grow at the same rate every year, investors required return stays constant, and both dividends and earnings grow at the same rate. In other words, it NEVER works. Companies grow faster during boom periods and slower during recessions. Required returns change when investors adjust their risk premium or inflation expectations. Some companies pay out higher yields (Altria) while others pay out no yields (Alphabet). However, Altria is expected to grow at about 5% while Alphabet is expected to grow at closer to 14% over the next 5 years.

If both companies earn $5 today, that tells us that in 5 years, Altria will be earning $6.49 while Alphabet will be earning $9.67. Clearly, Alphabet is worth paying a little more for today due to the higher earnings growth. Of course, how much more depends on (a) how long the earnings difference will last and (b) how big the earnings difference is. If the earnings differential is for 10 years instead of 5, then we’ll see the following EPS pattern (I’ve included actual, 4% vs. 6%, and 4% vs. 20% to illustrate differentials). As you can see, there is a lot of differences in the models.

Would you pay more for Altria or Alphabet? Obviously, Alphabet and the difference is based on how long (5 years, 10 years, or more) and what the differential growth rates are (is it a nearly 9% difference, a 2% difference, a 14% difference, or something different). Therefore, projecting how fast earnings are going to grow (which means revenues, expenses, interest, taxes, stock-based compensation, and a bunch of other factors) each year for the foreseeable future is necessary. Damn, I knew this picking stocks game was going to be tough, but really? And, unfortunately, yes…it really is this tough. That said, if you don’t have higher than anticipated dividend/buyback yield or change in PE multiple, you are going to need higher growth to justify an opportunity.

The PE Multiple

How much should I pay for a each $1 that the company earns? Well, the answer depends on the forecasted earnings growth from now through the end of time (pretty easy call, right?). Remember, when you buy a share of stock, you are buying a piece of the company. Therefore, to figure out what the share of stock is worth, all you have to do is forecast every dollar that the company is going to make (you know, after accounting for all of their expenses correctly), know exactly when they are going to receive each dollar (was that a year 16 dollar or a year 18 dollar?), and then choose the exact correct discount rate (hmmm…my inflation expectation for the next 100 years is what again?). Sure, that sounds pretty simple.

Did I mention that this stock picking game was not exactly easy? So, what can determine the appropriate multiple to apply a few years out? One factor is obviously going to be the growth rate that you assume. We know that an individual company cannot outgrow GDP forever without overtaking the world. Now, obviously it can for quite awhile, but if the company grows at 8% per year forever and GDP grows at 3% forever, sometime in the next hundred or so years, there’s going to be a bit of a problem. Let’s say that company X is a $10 billion dollar company and that global GDP is $81 trillion. Obviously a pretty big gap. However, let’s compound GDP at 3% for the next 100 years and we get that to grow to $1,557 trillion and the $10 billion company is now worth $21.998 trillion. In 200 years, the $10 billion company is worth $48,389 trillion and the global economy is worth $29,9217 trillion.

It seems like somewhere we run into a problem. If a company is growing faster than the economy, eventually, the company becomes LARGER than the global economy. I started with a company that is only worth $10 billion. What happens if I started with Apple — currently worth $2.5 trillion. It would only take 100 years to make that grow to $5,500 trillion vs. global GDP of $1,557 trillion (and yes, I recognize that global GDP is a yearly production number and market cap is based on the present value of all future cash flows, so it is not a perfect comparison). No company can grow faster than GDP forever. Eventually, either the company becomes global GDP or growth slows.

So, if a company can’t grow faster than GDP forever, what happens? Ultimately, the companies growth rate must slow (or GDP rise). Most forecasts go out about 5-10 years and then assume a constant growth (which is as unrealistic in 10 years as it is today). However, it does postpone the error a bit and (with time value of money) make it less of an issue. Unfortunately, if our required return is lower due to lower inflation, then so to is the reduction in error. In 10 years, an error of $10 in price is equivalent to $3.86 today at a 10% required return. On the other hand, if the required return is only 7%, that same error is $5.08. Therefore, our required return does make a difference.

The required return also makes a big difference in the pricing error 10 years out. If the company is going to pay a dividend of $3.00 in year 11 (which would be our D1 for year 10), have a required return of 10%, and grow at 3% per year, the price would be $42.86. However, if the required return was only 7%, the price would be $75.00. As you can see, that’s a big difference. And if the actual dividend was $3.15, that would make the price $45 (a $2.14 increase) vs. $78.75 (a $3.75 increase).

There’s also a legitimate argument that the “E” in the PE multiple is less meaningful in today’s firms than it was in the firms of the 1970’s. That is because many companies have realized that they can use intangible assets (things like R&D, corporate culture/employees, patents, etc.) to add value beyond net income. A lot of this is discussed in this article by James Weir. In one point, he refers to a study in which Kai Wu finds that

tangible assets make up less than 45 per cent of total value in six of the 11 sectors that make up the S&P 500, with things like network effects, brand equity, human capital and intellectual property making up the balance but not even rating a mention in financial statements.

and that

with back tests producing annualised returns more than 30 per cent higher than the S&P 500 over the past 25 years.

Granted, they used back tests which tell us what DID HAPPEN, instead of what is GOING TO happen. However, it does illustrate that the appropriate PE multiple is less about what the financial statements tell us and more about market perception (are people optimistic or pessimistic), what growth rates are expected to be (high or low and for how long), and the value of intrinsic assets (which are becoming a bigger portion of today’s balance sheets).

Putting It Together

Okay, so there are three things that influence your return:

Dividend/Buyback Yield

Earnings Growth

PE Multiple

However, these three things are somewhat correlated. Firms with higher dividend/buyback yield will tend to have lower earning growth. Firms with higher earnings growth will tend to have higher PE multiples. Notice the key word there is tend. Often, firms with higher dividends exhibit slower growth. However, this is not automatically true in companies that don’t pay dividends (Berkshire Hathaway and Alphabet have not paid dividends) sometimes grow quite well. Firms with higher growth usually have higher PE multiples, but what about companies like Snowflake that have high sales growth, but a negative multiple as their EPS is negative? Obviously, their expected growth is high, but how high and for how long? The key is that if you want to spend a whole lot less time on investing, again, let me recommend low-cost, passive ETFs with expense ratios under 0.20% per year (Vanguard Total Stock Market Index Fund ETF has an expense ratio of 0.03% per year and the Energy Select Sector SPDR Fund has an expense ratio of 0.12% per year). These are cheap funds and allow you to simply save and adjust your asset mix about once a year. However, if you want to try to your hand at investments and are willing to put in the work (recognizing that you are still going to be wrong…a lot!), you can do so. Just recognize that it is a tough game with few winners. That said, it is hard for me to see what happened with GameStop or Peleton and argue that markets are 100% efficient.

So, recognize that everything looked awesome for Peloton in July when the stock was at $130 (heck, even more so when the stock was trading for $170 in January, 2021). However, the story quickly collapsed. The ability to identify (and trade on these stories) is really, really, really hard. That said, the opportunity is there if you are one of the reasonably few who can do it.